Zohre Elahian: On the Responsbility to Others

With the goal of harnessing the untapped potential of Iranian-Americans, and to build the capacity of the Iranian diaspora in effecting positive change in the U.S. and around the world, the Iranian Americans’ Contributions Project (IACP) has launched a series of interviews that explore the personal and professional backgrounds of prominent Iranian-Americans who have made seminal contributions to their fields of endeavor. We examine lives and journeys that have led to significant achievements in the worlds of science, technology, finance, medicine, law, the arts, and numerous other endeavors. Our latest interviewee is Zohre Elahian.

Zohre Elahian is Managing Director of the Global Catalyst Foundation in Silicon Valley and has been actively involved in international development for close to two decades. She is co-founder of Schools Online, a not-for-profit organization that has brought computers to schools and introduced ICT in education in many countries around the world and within the US.

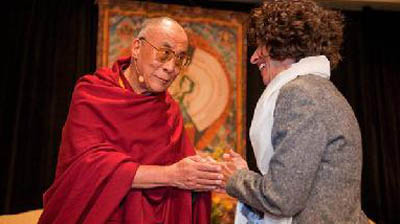

As the Managing Director of Global Catalyst Foundation, Ms. Elahian has also evaluated many projects, addressing critical needs in education and technology, ICT, and microfinance; her Foundation has provided funding to such projects in many countries. She has also served on the Board of Directors of Relief International for over 8 years, working on different developmental and humanitarian projects in countries such as Lebanon, Palestine, Sudan, Jordan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Iran, and many others. Prior to her humanitarian activities, she co-managed a successful private business for 15 years. She is currently on the board of Partners for Sustainable Development, a local NGO in Palestine, Goorulearning (Educational platform), Polyup (Computational Thinking EduGame company), and the Iranian American Women Foundation. In 2009 Zohre received the Unsung Heroes of Compassion award and a special blessing from His Holiness, The Dalai Lama.

Tell our readers where you grew up and walk us through your background. How did your family and surroundings influence you in your formative years?

I was born in Mashhad, Iran to a middle-class family of educators. My mother was a high school math teacher and my father was the principal at the same all-boys high school. We moved to Tehran after my parents were forced to resign from their jobs due to their religious beliefs. I went to public school through grades K-12 and pursued the social sciences at university. I was a student of history and political science at the University of Tehran and moved to the U.S. one year prior to the Islamic Revolution. I continued my education in the U.S. in the fields of anthropology and economics. After graduating from college, I began my own business. My parents, siblings, and my husband have been the greatest influencers in my life by providing me with unconditional love — it has been an amazing journey.

How did your upbringing influence your embrace of a humanist philosophy?

My parents’ families became refugees and were relocated to Mashhad/Iran after the Russian Revolution. They were forced to leave everything behind and came to Iran with only two pieces of luggage to their names. I will always remember the photo of my mom at age 9, standing in front of a carriage on the border of Turkmenistan and Iran. After the Islamic Revolution, my two brothers had to leave Iran through underground means because of their religious beliefs (followed by my parents). They lived as refugees until they settled in Western countries, and due to their educational backgrounds, assimilated into their new surroundings and achieved success and happiness in their new homeland.

I think, intuitively, the background of my family and many people around me impacted my humanitarian work including my strong belief in the importance of education as an equalizer.

What is the biggest challenge you have overcome in your career?

I always feel blessed to have the opportunity to work in areas where catastrophe has struck, serving various communities that have experienced the ravages of civil wars or natural disasters. The challenge is always returning home to a comfortable life in Silicon Valley. The paradox of these two worlds in leading a balanced life always remains a challenge.

Can you tell us what inspired you to undertake such a generous philanthropic program?

My turning point was on our first visit to Gaza in 1999. As part of our initial trip, we went to a refugee encampment (Beach Camp) and met with a family of refugees. The head of the family was a middle-aged gentleman with a big smile on his face; he explained that he had three children and his mother living with him. Their dwelling consisted of a small room with a stove in the corner and half of the ceiling in a state of collapse. He shared that he had a master’s degree in physics; he had graduated from a university in Moscow but now had no means of work and was living on the support of UNRWA. While he was talking to us, the smile never left his face. I quietly asked him, “Why was he so happy? Why wasn’t he frustrated and angry with the situation that had been imposed on his family?” He then asked me to follow him outside and we found ourselves on the beach with a stunning view of the Mediterranean Sea. He looked to the sea and said, “Why shouldn’t I be happy? Whenever I get down, I come outside and look at this view, what else could I want?” As we talked further, he shared that, more than anything, he wanted his children to receive an education and have access to the outside world. On our way back to the U.S., I told my husband that I was going to leave the company I had created. I wanted to begin helping refugees in disaster areas, and I did that within a few months of our first visit to Gaza.

Can you elaborate on the different countries in which you have worked?

With respect to a geographical presence, I have been directly involved in implementation on the ground in the following countries:

– In Africa, we have worked with Burundian refugees in Tanzania, internally displaced people (IDP) n Darfur/Sudan, an education and technology project in Namibia, and an education project in South Africa.

– In Asia, we have helped IDPs in Afghanistan, and have been active in disaster relief and development in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Iran, and have run an education project in Azerbaijan for refugees and IDPs from Nagorno-Karabakh. In Jordan we have worked with Iraqi refugees, integrating technology in education. We have worked on development and education projects in Lebanon, and educational and entrepreneurship projects in Palestine (Gaza and West Bank).

In all our projects, we have focused on education, technology, women’s microcredit & business development, and entrepreneurship.

How does your experience as a successful entrepreneur inform your work as a philanthropist?

I am not sure if I can call myself a successful entrepreneur but thank you for the compliment, I love it. The world of philanthropy and humanitarian work is very similar to the world of entrepreneurs and innovators. Our community identifying such would ideally focus on design thinking, implementation, and scaling. At many levels, the work of entrepreneurs and philanthropists overlaps. A philanthropist needs to develop innovative ways to have high impact and scale projects. One always runs the risk of failure, but you can lower that risk by engaging the community and ensuring the ownership of the program is in the hands of the local community. Entrepreneurs will do the same; by disseminating the shares among the staff and involving them in all aspects of the decision-making to ensure the success of the company.

What have you found to be the biggest differences between funding education in the States and funding education overseas?

The education system in the U.S. is decentralized and it is challenging to get into the system as an influential actor. The disparity in the U.S. education system is vast and has created inequality in the opportunity to learn. In the developing countries where I have worked, while disparity certainly exists, there is greater room for having a nationwide impact. In developing countries, they are more receptive to new educational innovation, while in the U.S., the education market is overflowing with EdTech companies.

Which of your philanthropic endeavors are you most proud of?

The ones that the community got involved in from day one and ended up with 100% community ownership of the project. For example, our (Global Catalyst Foundation) project in Tanzania bringing electricity, access to the Internet, providing computer labs and educational workshops for Burundian refugees and the local hosting community in 2002.

Most recently, the NETKETABi project in Palestine which started in 2011 in collaboration with OPIC and is now a nationwide project and has been transferred 100% to local ownership.

What advice would you give to donors who are interested in supporting education programs for young people?

We need to bear in mind that education is an equalizer, so we need to be mindful that the educational project must be inclusive, scalable, and will be owned by a local community. In addition, life skills, learning about community service, and learning first hand by being an integral part of the project is at the heart of any educational project.

What advice would you give to a fellow donor who is thinking about starting to give overseas?

Giving should not be limited to writing checks; it is ideal if you visit the project that you are planning to support and see what needs to be done, in addition to the monetary contribution. There is a dynamic relationship between the contributor and recipient, the two benefit one another, and that only can happen when there is direct contact between human beings.

Looking ahead, what are your future philanthropic plans? Are there any charitable endeavors you would like to undertake but haven’t yet?

I am becoming more focused on education and the use of technology to expand access to education; geographically focusing on West Asia. In addition, I am partnering with my husband, Kamran Elahian in the various initiatives he is developing for high-tech entrepreneurs in West Asia and Africa region. As far as my work in the U.S., I have been involved in an EdTech company, Polyup (www.polyup.com), with a tremendous social impact focusing on math / computational thinking and learning through doing. One of my goals is to take Polyup to developing countries and children in refugee camps.

There are no charitable efforts that I wish to work on but haven’t yet. I have been fortunate to act upon what I wish to do in my humanitarian work.

Can you share your thoughts on your Iranian-American identity? What does it mean to be an Iranian-American to you?

This is a challenging question, as I see myself as a global citizen; a person with no official religion and not believing in borders and boundaries. I truly believe in the equality of humanity and practicing it daily. I think religion and nationalities are working against equality and humanity by creating division and separation. Wherever I worked, I have felt at home and I became one of them, which is the beauty of the world we live in.

I love this section of Rumi’s poem:

“Not any religion or cultural system. I am not from the east or the west, only that breath breathing human being.”

“Jahandad Memarian, Media Advisor at the Iranian Americans’ Contributions Project (IACP)”